The Promise of Genomic Sequencing and the Unwelcome Surprise

Genetic testing via panel testing, whole-exome sequencing (WES), or whole-genome sequencing (WGS) promised clarity. The hope was that we could identify disease-causing variants, provide diagnoses, and guide patient care. Yet for many patients and research subjects, the result is uncertainty. Instead of a clear, actionable variant, they receive a large list of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS). These are DNA changes that cannot be confidently classified as benign or pathogenic.

For clinicians and labs, VUS are not rare oddities. They are common outcomes in current workflows. For many patients, a VUS result means no actionable guidance. For labs, it means growing backlogs of ambiguous variants. Even as sequencing capacity and data resources expand, the VUS bottleneck persists and in many contexts becomes worse.

This post explains why this occurs and why the inherent design of variant interpretation ensures the bottleneck remains unless we add a fundamentally new type of evidence.

What a VUS Is and Why So Many Variants Fall Into That Category

In clinical genetics, variants are typically classified into five categories: benign, likely benign, VUS, likely pathogenic, and pathogenic. A VUS is assigned when available evidence is insufficient or conflicting. For example, a variant may be extremely rare or novel, absent from population databases, lack functional studies, or produce computational predictions that are ambiguous or conflicting (Burke et al. 2022).

Because each human genome contains thousands of rare or private variants, many of them never observed in any cohort, VUS are not rare phenomena. In contexts such as rare-disease panels, oncology panels, or broad exome sequencing, VUS often make up the majority of non-benign variants. The burden is real: patients may receive no definitive interpretation. Clinicians face uncertain risk assessments. Labs accumulate VUS for potential re-analysis indefinitely.

The Growing Scale of the Problem: VUS Is Not Diminishing

Despite improvements in sequencing, larger reference datasets, and better annotation tools, VUS remain pervasive. In some cases their prevalence increases as testing expands or becomes more inclusive.

In a 2023 large-cohort study of 1,689,845 individuals who underwent hereditary disease genetic testing, 41.0% had at least one VUS, and 31.7% had only VUS results (no pathogenic or likely-pathogenic variant). The number of VUS per individual increased with panel size. Missense variants made up 86.6% of VUS changes (Chen et al. 2023).

In a hereditary cancer syndrome testing, reported VUS rates range between 10% and 40% depending on the gene panel and patient population (Chrysafi et al. 2023).

A broad review highlighted that because of the high baseline frequency of rare and novel variants in the human genome, VUS remain a persistent challenge in clinical genomics (Burke et al. 2022).

These data show that broader testing, higher panel complexity, and increased population diversity lead to more uncertain results rather than fewer.

Why Conventional Tools and Data Fail to Solve the VUS Crisis

Given extensive population databases, computational predictors, and knowledge of functional assays, why has the VUS burden not declined? Because of structural limitations in the types of evidence available.

Rarity does not guarantee pathogenicity

Filters based on population frequency help exclude common benign variants. But absence from these databases does not prove that a variant is harmful. Many benign variants remain rare because they are private to a family or come from under-sampled populations. As a result, rare benign variants can still be labeled VUS (Burke et al. 2022).

Computational predictors remain imprecise

Prediction tools, whether conservation-based metrics or advanced machine-learning models, are widely used. For rare or novel missense variants, which form the bulk of VUS, these tools often produce ambiguous or conflicting predictions. Their performance declines when applied across diverse genes or when functional data is lacking (Costa et al. 2025).

Functional validation is resource-intensive and rarely applied

Assays such as cellular, biochemical, or segregation studies are considered the gold standard for assessing variant impact. However, they are resource-intensive, low-throughput, and often impractical for the majority of VUS. Most VUS never receive functional testing and thus remain unresolved (Menke et al. 2021).

Population and clinical databases are biased

Many databases over-represent individuals of European ancestry and well-studied genes. Rare or private variants from under-represented ancestries or less studied genes may lack reference data. This increases the likelihood these variants are labeled VUS (Chen et al. 2023).

These structural limitations explain why even comprehensive modern pipelines fail to interpret many variants with sufficient confidence.

The Root Cause: Interpretation Is Limited by Evidence Types, Not Sequencing Depth

In our opinion, the fundamental issue behind the VUS bottleneck is not insufficient sequencing data. It is insufficient diversity in the types of evidence we use for interpretation. Current workflows rely largely on:

- Human population data (frequency, co-occurrence)

- Computational predictions and occasional functional assays

Both of these depend on human variation, which is inherently limited and biased. Sequencing has expanded horizontally (more samples, more genes) but we have not expanded vertically — in the sense of deeper biological context or orthogonal lines of evidence. As data volume grows without new evidence dimensions, uncertainty scales in parallel.

How Evolutionary Context Offers a Third, Independent Axis of Evidence

Comparative genomics (using evolutionary history across species) provides a powerful and under-utilized third axis of evidence. Over millions of years, genes and proteins have experienced natural selection. Variation tolerated in related species implies functional permissibility. Variation purged over time implies functional constraint.

If a missense variant is observed and tolerated across multiple non-human primate species, that suggests the amino-acid change is permissible in a biologically relevant context. Conversely, a variant appearing only in humans and never across deep evolutionary history could indicate risk.

This evolutionary context offers evidence independent of human population sampling. It is grounded in biological function rather than statistical inference alone. It is also inherently more equitable across ancestries, since it is species-wide rather than demography-specific.

Comparative genomics adds a third axis of evidence. It complements population data and computational predictions. It provides a path forward to reduce VUS burden.

We explore this evolutionary approach in more detail in another post titled “Why Evolution Is the Missing Dimension in Variant Interpretation.”

What Evolutionary-Informed Interpretation Could Do and Why It Matters

If evolutionary evidence is integrated systematically into variant interpretation pipelines, it could transform the process:

- Many rare or novel variants might be reclassified as likely benign if they are observed and tolerated across related species.

- Labs and researchers could triage variants more quickly, without waiting years for more human data or functional assay results.

- Interpretation would become more global and equitable. Because evolutionary evidence is species-wide, it reduces reliance on human population sampling and mitigates ancestry bias.

- The approach would scale across all genes, including poorly characterized ones — precisely those where VUS burden tends to accumulate.

- Clinical and research resources could be directed toward variants with real potential. Time, cost and effort would be used more efficiently.

Why the Status Quo Is Insufficient and What Must Change

The ongoing VUS burden demonstrates clearly that generating more sequencing data alone will not reduce uncertainty. More data without new evidence types only creates more ambiguity. The field must evolve its methods. It must combine human data, computational annotation, and evolutionary evidence.

Clinical labs, diagnostic centers and research institutions should adapt their workflows accordingly. Researchers and tool-builders should invest in comparative databases, cross-species alignments and functional-constraint analyses — not just collection of more human genomes.

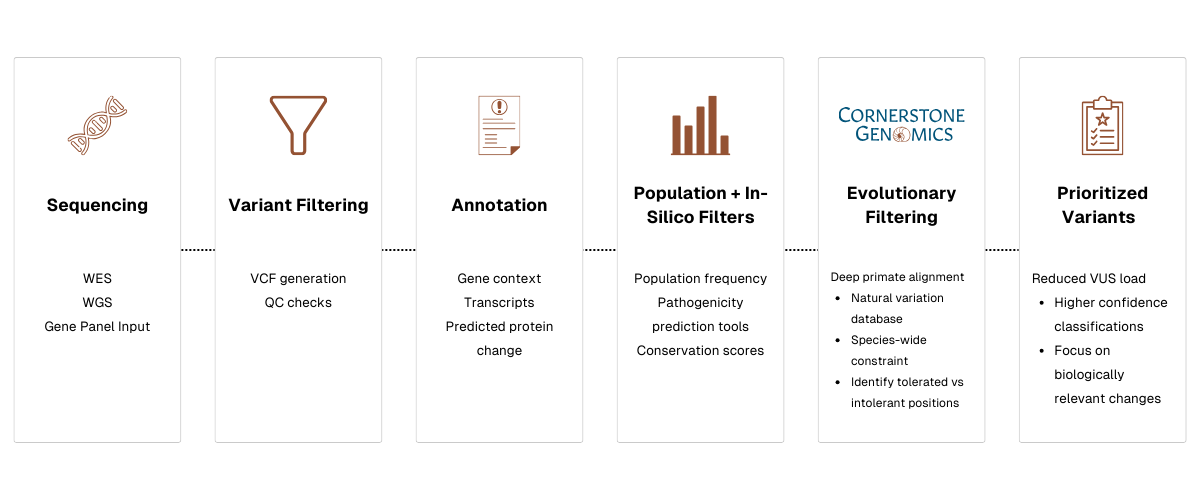

How Cornerstone Genomics Is Building the Bridge

At Cornerstone Genomics we treat evolutionary evidence as essential. That is why we built a platform that aggregates primate exomes across dozens of genera into a unified, aligned database and integrates that evolutionary context directly into variant interpretation.

Our internal studies demonstrate three foundational findings that support the power of evolutionary evidence:

1. Pathogenic variants do not co-occur with natural variation

Across ENIGMA, ClinGen, and BRCA Exchange datasets, pathogenic variants curated by expert panels were unique to humans, while benign variants were shared across primate species. (Cornerstone Genomics, internal validation study)

2. BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS can be reduced by nearly 30%

In our BRCA1/2 analysis of 2,551 SNPs, nearly 30% of VUS and conflicting classifications were clarified as likely benign using evolutionary evidence. (Cornerstone Genomics BRCA1/2 Study)

3. Across ~14,406 genes, ~20% of VUS can be confidently reclassified

At a genome-wide scale, CodeXome reclassifies approximately 20% of ClinVar VUS missense variants to likely benign, with gene-specific ranges of 10% to 40%. (Cornerstone Genomics ClinVar VUS Study)

These findings support the principle that evolutionary evidence can systematically reduce uncertainty in variant interpretation at scale.

By layering evolutionary context on top of population data and computational predictions, our platform helps reduce the VUS backlog, prioritize variants more effectively, and provide greater interpretive confidence — often in minutes.

We view evolutionary context not as a niche add-on. We view it as a foundational pillar of variant interpretation.

What This Means for Researchers, Clinicians, and Labs

If you work with genomic data (whether rare disease, cancer genetics, pharmacogenomics, or basic research) then when you encounter a VUS result, consider asking:

- Could the variant be rare simply because human sampling is incomplete rather than because it is harmful?

- Would evolutionary context help determine if the amino-acid change is tolerated across species?

- Could integrating evolutionary filtering into your interpretation pipeline accelerate interpretation, reduce uncertainty and increase confidence?

If you are planning sequencing studies, especially broad gene panels, exomes or genomes, consider designing a hybrid workflow from the start. Combine human population data with computational annotation, and add evolutionary evidence to maximize interpretability and minimize uncertainty.

Conclusion: A VUS Crisis That Requires a New Perspective

Genomic sequencing has transformed medicine and research. Yet our tools for interpreting variation have not kept pace. As sequencing becomes more widespread, the backlog of uncertain variants (VUS) continues to grow. That is not a flaw in sequencing technology. It is a limitation in how we interpret genetic variation.

Unless we expand the evidence paradigm beyond human data and computational predictions, the VUS bottleneck will remain. Incorporating evolutionary genomics introduces a critical dimension: biological context grounded in deep time rather than human sampling alone.

At Cornerstone Genomics we are building tools to make that shift practical and scalable. In a world of near-infinite variation, only evolutionary history may bring clarity.

If you want to explore how evolutionary filtering performs on your data or discuss collaboration, our scientific team is ready to connect.

References

- Chen E, Facio FM, Aradhya KW, et al. 2023. Rates and Classification of Variants of Uncertain Significance in Hereditary Disease Genetic Testing. JAMA Network Open. 6(10): e2339571. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2810999

- Burke W, Parens E, Chung WK, Berger SM, Appelbaum PS. 2022. The challenge of genetic variants of uncertain clinical significance: a narrative review. Annals of Internal Medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10555957/

- Chrysafi P, Jani CT, Lotz M, et al. 2023. Prevalence of Variants of Uncertain Significance in Patients Undergoing Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes. Cancers (Basel). 15(24): 5762. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/15/24/5762

- Costa M, Reardon J, et al. 2025. The promises and pitfalls of automated variant interpretation. Briefings in Bioinformatics. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12513165/

- Menke C, Noll J, et al. 2021. Understanding and interpretation of a variant of uncertain significance by non-genetics providers: a qualitative study. Journal of Genetic Counseling. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jgc4.1422